Coyotes

Coyotes on Long Island: Background

The following videos, from presentations made by Gotham Coyote founders Mark Weckel and Chris Nagy at the 2015 Long Island Natural History Conference, (while already slightly outdated) provide excellent background about how coyotes arrived in our region and what can be expected about their colonization of Long Island.

Dr. Chris Nagy: New York’s Newest Immigrants – Coyotes in the Metropolitan Area:

Dr. Mark Weckel: Coyotes on Long Island, a Framework for Planning Ahead:

The Long Island Coyote Study Group is a coalition of government officials, academics and nonprofits working to monitor the coyote colonization of Long Island and research their ecological impacts. Members of the group are also engaged in efforts to educate Long Islanders about coexisting with coyotes. Participants include representatives from the following:

American Museum of Natural History

Brookhaven National Laboratory

Concerned Long Island Mountain Bicyclists (CLIMB)

Greentree Foundation

Hofstra University

Kingsborough Community College

Mianus River Gorge Preserve

NYS Department of Environmental Conservation

NYS Parks – Long Island Region – Environmental Office

Seatuck Environmental Association

Wild Dog Foundation

Is it a Coyote?

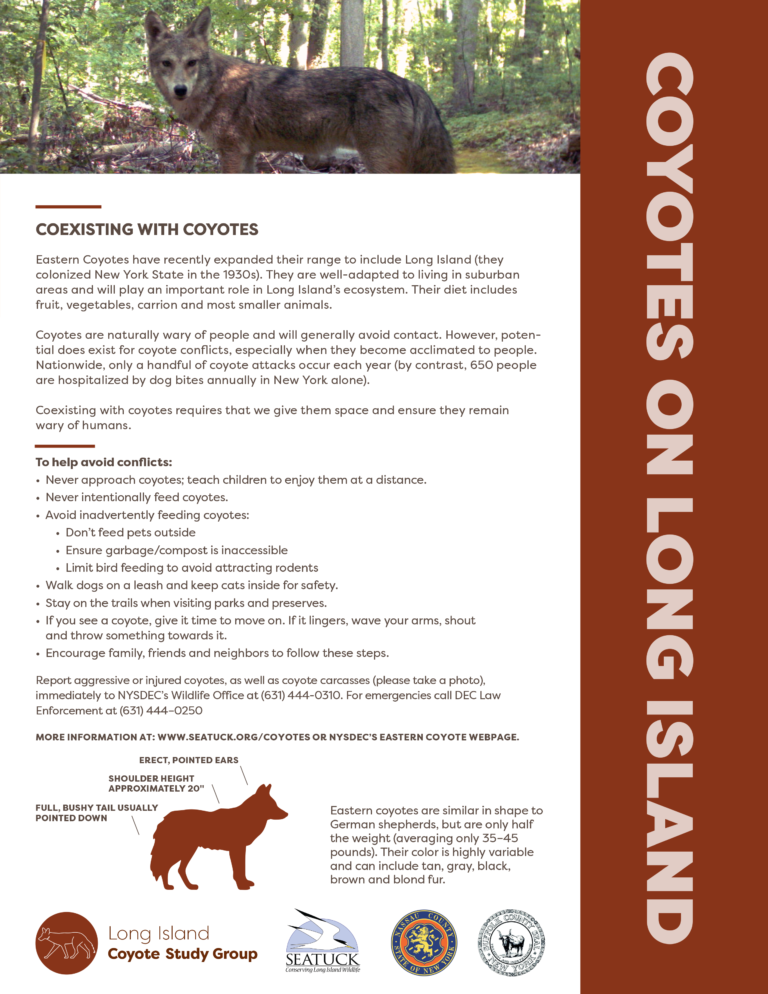

Eastern Coyotes have a wide variety of pelage colors. Most have a mix of gray, white, brown and black banded hairs, but it’s not uncommon for some to be a very uniform tan, blonde or golden color. A key ID feature is its bushy tail that usually hangs straight down (domestic dogs, with a few breed exceptions, have curled tails). Most coyotes also have a black-tipped or dark-tipped tail and a distinct black or dark mark just below where the tail attaches to the rump. The latter marks a scent gland.

Note the arrows pointing to the black tipped tail and black spot over the scent gland. This coyote is sporting its short, summer coat making it look relatively lean and long-legged.

Coyotes sporting a uniform gold or tan color are not uncommon. This coyote, photographed on Fishers Island, is in its winter coat, making it look relatively short-legged and husky. The tail’s dark tip is just visible.

(Tracy Brock photo)

This malnourished pup was found in a Pennsylvania state park and initially thought to be a shepherd mix puppy. Based on the circumstances in which she was found, the rehab center decided to run a DNA test. The results revealed that she was a coyote.

Most mistaken coyote ID photos that we’ve received on Long Island are of young red foxes that haven’t yet developed their adult pelage. Red foxes have white-tipped tails, black feet, and black on the lower legs. Be aware that the white-tipped tail isn’t apparent from all angles, and black hairs on the lower legs are concentrated on the forward-facing part of the leg and may not be discernible from the rear. They also have black ears; these are best viewed from behind or the side. It’s difficult to mistake an adult red fox for a coyote, but the young-of-the-year don’t always look very “foxy.”

ABOVE: Adult red fox in its winter coat. Note the clearly visible black ears, black feet and black lower legs, yet the white-tipped tail is not apparent from this angle.

BELOW: Adult red fox with all the key ID markings visible.

ABOVE: As is the case with the coyote, the red fox in its summer coat looks more “leggy” and its bushy tail seems oversized for the individual. Yet you wouldn’t mistake this individual for a coyote.

BELOW: Note the amount of gray fur on this adult female nursing her tan and gray colored young (Last Photo). The pup’s black ears are evident, as are their white-tipped tails, but the tails are not bushy. The most common mistaken coyote ID is of the young red fox pups with their tan and gray coats, such as the one photographed below, whose key ID features (white-tipped tail, black ears and black lower legs) are visible but easy to overlook.

Coyotes on Long Island: Will They be Good Neighbors?

Wildlife is in trouble around the globe. From tiny frogs to top carnivores, there has been a flood of research in recent years documenting the grave situation many species face. Even some of our most charismatic megafauna are at great risk. And new research lends support to the argument that we’re in the midst of the planet’s sixth “major extinction event.”

Remarkably, despite this distressing overall trend, Long Island is in the paradoxical position of welcoming a new species. Not a once-extirpated species that has been recently reintroduced, or an exotic species that established here after being unintentionally released, but rather a top carnivore, the Eastern Coyote, that is in the process of expanding its range to include Long Island.Coyotes historically lived only in the western and central United States, where they thrived in the prairies, deserts and wide-open country for which they are especially well suited (and famously known). Their range was limited to niche habitats by larger predators, including wolves, bears and cougars, which dominated richer, forested habitats like those found in the eastern part of the country.

But with humans clearing forests and mercilessly persecuting larger predators, coyotes found themselves with some room to roam. And roam they did. Over the past 100 years, coyotes have expanded their range eastward to include the entire continental United States and southeastern Canada. They’ve also expanded further northwest into Alaska and south into Central America (even South America is in their sights).

Coyotes have succeeded in every possible habitat, from the taiga of Canada to the citrus groves of Florida. They’ve even settled comfortably into urban areas: a healthy population roams Washington, D.C. and Chicago is home to several thousand coyotes. A few years ago, a coyote made headlines when it casually walked into a Quiznos in Chicago’s South Side and sat down in a beverage cooler!

The fact is most urban and suburban areas in North America are now home to coyotes. The adaptable animals (“behaviorally plastic generalists,” as scientists say) manage well on the margins of development and in between the areas of human habitation. They primarily inhabit out-of-the-way places in parks, greenbelts and industrial areas, survive on a wide range of food, and avoid humans by being most active at night. They are, according to experts, masters at hiding in plain sight.

Long Island is now the only major area left in the country (not including Hawaii) that coyotes haven’t colonized. But the process is underway. Coyotes are well established in Westchester and firmly ensconced in the parklands of the Bronx. As these populations grow, young adults are increasingly being pushed to explore Long Island for available territory (they can easily swim from parts of the Bronx, but they are more likely to walk across bridges and train trestles).

Long Island’s first official resident coyote settled into a small park in Queens as early as 2009. Reports of additional individuals followed in subsequent years, but the island’s first confirmed mating pair wasn’t documented until more recently. The young adult pair had been living in a narrow woodlot near LaGuardia Airport for years and went largely undetected before rearing a litter of eight pups in 2016. Even then, it was only when trees were cleared for a parking lot that they were discovered and problems arose. Their pups, still too young at the time to be moved far, eventually attracted attention. When people started feeding them, the Port Authority decided it had no choice but to remove the family to “protect the safety of its employees.” All but one of the coyotes were trapped and killed (see here for full details).

Despite the tragic results at LaGuardia, the coyotes have kept coming. Over the past few years, new individuals have continued to show up across northwestern Long Island. One even turned up at Robert Moses State Park on Fire Island earlier this year. With several mating pairs having now established in northern Nassau County, coyotes seem to have finally gained the foothold on Long Island that will be the springboard for their expansion. Scientists expect they’ll fully colonize the island within a decade.

To be clear, while episodes like what happened at LaGuardia may temporarily delay the process, there is little we can do to stop coyotes. For over a century, communities worried about perceived dangers to humans, threats to livestock or other concerns have failed to remove or keep coyotes out.

As word of the pending colonization spreads, Long Islanders, like many others before them, will reasonably be concerned about safety. But coyotes have demonstrated across the country that they can live harmoniously in proximity to people, even in densely populated areas. While some level of conflicts (including confrontations with people and pets) are inevitable, most can be avoided. But only if we take the simple, tested steps to prevent them.

The key is to ensure coyotes maintain their natural aversion to humans and have no reason to be in our direct proximity. Most significantly, this involves not making food sources of any kind available near homes or businesses. Study after study has shown that coyotes primarily rely on a natural diet, but they are opportunistic and will take advantage of food sources we create.

This obviously includes not intentionally feeding them. Coyotes that habituate to being fed are a potential risk and must be lethally removed (as wildlife managers like to say: “a fed coyote is a dead coyote”). But crucially, it also includes eliminating any unintentional sources of food, such as garbage or pet food. It also includes closely monitoring pets, especially at dusk or nighttime. It should surprise no one that small dogs and cats left alone at night are likely to attract the attention of a resourceful coyote living in a nearby woodlot. In this regard, a large burden will fall on pet owners to modify their behaviors and keep their dogs and cats safe. These and other simple steps – including aggressively scaring off any coyotes that do get too close – will help keep them away from our residences and eliminate most conflicts.

We know coyotes will colonize Long Island in the coming decades. And we know they can make good neighbors. We also know that by replacing missing apex predators, they’ll have a positive impact on our natural areas and the island’s overall ecological health. The only question is whether we’ll modify our behaviors and take the necessary steps to minimize negative interactions. In other words, the question is not whether coyotes will be good neighbors; the question is rather, will we?

For more information please contact Mike Bottini, Seatuck Wildlife Biologist, at [email protected] or 631-581-6908

Be a Good Neighbor!

How to coexist with coyotes on Long Island and help avoid conflicts

Avoid attracting coyotes

- Coyotes look for food and shelter, so avoid anything that might attract them to your yard

- Make sure any trash/compost/waste is secured if stored outdoors and try not to leave it out for long periods of time

- Keep any sheltered areas cleared out and closed off if possible, such as crawl spaces under porches, outdoor sheds, etc.

- If you have bird feeders, make sure the food is stored securely and regularly clean the areas around feeders, seeds on the ground invite small mammals like squirrels that attract coyotes

- Coyotes very rarely attack humans and have a natural aversion to people

- When dealing with a coyote, never turn and run from them because that can trigger their instinct to chase you

- Keep small pets on leashes when walking them, especially at dusk or nighttime

- Do not leave small pets alone and unmonitored in your yard, especially at dusk or nighttime

- If you do see coyotes in your area/property, make them feel uncomfortable until they leave, so that they are less likely to return

- Look big and be loud, yell at the coyote and advance towards it slowly until it completely leaves the area

- You can bang pots and pans, use noise makers or whistles, or spray a hose at it

- If the coyote is not moving or keeps stopping and turning to look at you, continue this behavior because they will eventually run away

- Throw small sticks or balls towards (not at) the coyote to scare them away

- You want to make them feel unwelcome/unsafe without actually causing any harm

- If you continue to do this when you see coyotes, they will stop returning for whatever thing they wanted there in the first place (usually food or shelter)

FAQs

With misinformation about coyote coexistence propagated

“Any wildlife biologist will tell you that you should not let your cats out at all, unless you have a fenced yard or some other enclosed outdoor space the cat cannot get out of. First, there are many things other than coyotes that are dangerous for your cats (dogs, cars, people, raccoons, hawks, etc. with cars being the big one). Cats can eat rodents that have already been poisoned with rodenticide (this happens to a lot of wildlife too, unfortunately).

Second, cats do great damage to birds, small rodents such as chipmunks, and other small wildlife. The animal’s domestic cats kill each year averages in the billions. Thus, my non-diplomatic answer to your question about whether coyotes eat cats during the day is if you don’t let your cat out you don’t have to worry about it, and by doing so you are also being a responsible pet owner and helping local wildlife thrive. A fenced yard if you are able, is a great way to let your cat have fun outside (it is what I have for my cat).”

“There are a few factors to consider here. First, the behavior of your community in regard to coyotes makes a difference. People feeding the local coyotes, either directly or indirectly, will make them spend more time in residential areas, along sidewalks, etc. In some cases, the coyotes will want to defend the territory and the anthropogenic food resources there from intruders, which could include your dog. They will become more accustomed to people as well, making them willing to consider defending their territory from the dog that they see as an intruder. So the number one thing is to avoid that sort of conditioning not only at the individual level but at the neighborhood level too.

The size of your dog matters. A dog bigger than 25 pounds is unlikely to be seen as a potential food item for a coyote. The only time a coyote has a decent probability (still very low) to bother a medium or large dog like that is if you approach them during the denning and pup-rearing periods. Pups are in the den from about April to June/mid- June, and if you happen to come close to a den (which only very rarely occur outside of natural areas) the adults will certainly watch you and likely not run away from you as readily as if they were alone. From late May to early July, the pups are still small but may be out of the den, so the adults usually stash them under a bush or in a log while they forage. If you come upon one of these hiding places, the adults may also behave more defensively — not running away, perhaps growling, watching you carefully, possibly following you for a time as you leave to make sure you are really leaving and not circling around to eat their young. They will be more on edge if you have a dog. If you see a coyote that is a bit more “bold” than you would expect (all the coyotes I have ever seen have run away from me if I was within 30 yards of it) there may be young nearby, and you should probably turn around and go down another trail. Usually by July the pups are very mobile so the whole family can avoid you and your dog without you even knowing they are there.

This assumes you have your dog on a leash. If your dog is off leash, it could try to chase the coyotes and the coyotes will either run, or, if there are young around, they may defend themselves and their families. I have gotten many complaints of a coyote attacking a dog, only to find out the owner was letting the dog run around the woods with no leash, and the dog found a den, or a pregnant female and the parents understandably defended their family. So off leash is a whole other story and is not a good idea for your dog; even if there are no coyotes in your area, there still are roads and cars, skunks, and raccoons (that potentially have rabies). In a residential area, coyotes are very good at avoiding people and don’t look for trouble. If you walk your dog around dawn you might see them running through. But by-and-large there is nothing to worry about if the coyotes are kept wild and do not get food from anthropogenic sources. If you have a small dog, keep them on a leash, and if a coyote does approach it may be thinking about its chances of grabbing the little guy out from under you. In those cases, you can yell or use various noisemakers, or pick up your little dog. These incidences are very rare and, again, are usually the end result of many months or years of people conditioning the local coyotes (feeding by hikers or residents, mainly) to not be afraid of people.”

“There are several reasons why population control is not a feasible or reasonable idea generally for coyotes. First, coyotes are legally protected and native game animals in New York State. So, the fact they are occurring here is not abnormal or unexpected, nor something that needs to be “fixed.” There are of course legal methods of removing individual problem animals but removing the species as a whole is not legal.

That said, the DEC may open hunting and/or trapping seasons for coyotes in Long Island in the future if the population is deemed able to support it. This is often the means by which the state biologists’ “control” a population if they are deemed overabundant.

Biologically, coyotes generally regulate their own densities. They are very territorial, so there will only be a single mated pair in any given area. Wanderers may come through or live in the same area by avoiding the resident pair, but these ‘transients’ are not breeding. So, density is naturally regulated by food availability and space. Usually, young coyotes leave their parents sometime between the age of 6 months to 18 months old. They will either try to find a “vacancy” in the landscape or barring that try to disperse a very large distance into a whole new area. (This process is how coyotes expanded across all of North America, including now Long Island).

Lastly, people have tried to eradicate coyotes in the US for 200 years or so, and now they are the most widespread (wild) canid in the western hemisphere. Trapping them is very difficult and the removed coyotes are quickly replaced by new ones when the transients I mentioned fill in the newly vacant territory. If resources are abundant, a single female can have 15 or more pups in one litter.

Birth control techniques/protocols as far as I know have not been developed for coyotes, but I imagine it would be very expensive and hard to catch enough of a portion of the population to make any difference. Again, I first would want to objectively evaluate the purpose and rationale that is used to determine whether a population needs ‘control’ in the first place. This is especially true for a species that regulates its own density, has proven largely impossible to “control” despite herculean (and rather horrifying) efforts on our part, and does not tend to down-regulate its own prey base (coyotes are a very generalist carnivore, so if one food type becomes rare, they switch to something else. Predators like this do not typically cause negative impacts on prey populations).

As I said, if individual coyotes are behaving badly or causing damage, eating livestock, etc. there are ways to change their behavior or stop them from causing the damage, and if necessary, to legally remove those individuals.”

“Number 1 thing is to not ever feed them. Coyotes are very smart, and they can quickly make an association between people and getting or finding food. Once this pattern starts, they might start to experiment and become more comfortable exploring “human spaces” instead of staying mainly in the woods and just moving quickly through the neighborhood in the middle of the night. If this proves profitable for them, they might start to eat a few cats, wander around people’s yards, etc. So, if they continue to get

closer to people and yards and houses and this continually provides food or other resources, then it escalates until there is a real problem.

Along those lines, I try to convince people that coyotes are fascinating animals and seeing one should bring a feeling of excitement, not fear. But of course, there is a balance, and they should be enjoyed from a distance. People should not go looking for them, or try to chase them, or try to find their dens, or try to lure them closer for a selfie with food, or whatever. They are wild animals and should be appreciated from afar.”

Press Coverage

Related Information

Press Release: Coyote Colonization Gathers Steam

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 1, 2020 Contact: Arielle Santos, Policy Program Coordinator – 631-278-5601, [email protected] Coyote Colonization of Long Island Gathers Steam ISLIP, NY: Coyotes are no longer just coming to our region,

Coyote Tracker

Coyote Tracker is a community science project that engages Long Islanders in the effort to monitor the colonization of our region by Eastern Coyotes.

Newsday Opinion: Coyotes on Long Island

Is Long Island a New Habitat for Coyotes? Newsday – September 13, 2020 By Enrico Nardone Despite the trouble that wildlife is in around the globe, Long Island is in the paradoxical position of welcoming a new top carnivore: The